A stone’s throw from the Arc de Triomphe, in the smart 8th arrondissement of Paris, a stranded flaneur may bump into the most improbable sight: a three-story, imperial red Chinese pagoda, with hipped roofs and latticed windows, nestled among fin de siècle Haussmannian architecture. Built in the 1920s, it used to house one of the first art galleries in Europe specializing in Chinese art, owned by the legendary art dealer C. T. Loo, and serves to illustrate the long-standing Chinese presence in Paris.

While the most visited city in the world is primarily associated with quintessential European elegance, in fact it is also a vibrant cosmopolitan metropolis where various cultural groups have made their home. The permanent presence of a Chinese community in Paris dates back to the late 19th century. The two Parisian Chinatowns – in the 13th arrondissement and in Belleville – are further proof of the ongoing arrival of immigrants from China, as are the numerous trendy Chinese restaurants popping up in most parts of the city. Today, Paris offers the best baguette and some of the best dumplings within a one-kilometer radius.

For more than a century, Paris has been attracting artists, students, and intellectuals from China, seeking new inspiration, novel techniques, and creative spaces in the studios, schools, and salons of what used to be the capital of the art world. But when the first of them arrived, they were not the only ones seeking to make a name for themselves on the glamorous and carefree cultural scene of the Ville Lumière. During the late 19th century and the first decades of the 20th century, artists from all over the world moved to Paris to study art. Chinese art students began going to Paris after World War I, partially supported by a program organized between the Chinese and the French governments.

In Western art historical discourse, this period provides a canonized chapter of the Eurocentric narrative of artistic Modernity. It is associated with the overcoming of classic figurative painting, and the shift towards Modernism. However, while Cubism was transforming painting into sculptural assemblages, foreign artists were still coming to France, and Paris in particular, in order to master the academic techniques of painting and drawing that the avant-gardes groups were in the process of abandoning.

Students from China, for example, came to learn the forms of scientific representation that did not exist in traditional Chinese painting. Academic realism, never used before in China, was ‘Modern’ from the perspective of a Chinese art student in the 1920s. Traditional Chinese painting centers on the dexterous use of the brush, aimed at establishing empathy between the artist and the object. Paradoxically, this is close to what the Abstract Expressionists sought to achieve and considered a major innovation, 30 years later.

In the 1920s, Western Academic painting was centered on the human figure, most often represented in the nude – a subject that barely exists within Chinese artistic traditions. This explains how nudes are a recurrent subject in the work of Chinese artists who came to Paris in the interwar period. Sanyu (Chinese name Chang Yu) arrived in 1921 and chose to attend a private art academy instead of the more rigorous École des Beaux-Arts. Many of his earliest, and now most prized works, represent nudes or fellow female students in the act of drawing during classes at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière.

Sanyu adopted a loose style which diverged from the accurate form of representation typical of academic training, choosing the suppleness of the ink line to suggest volume. Henri Matisse’s popular silhouette paintings inspired Sanyu and gave him confidence in his ‘Eastern’ approach to Modernism. For Sanyu, the French Fauvists, with their loose brushwork and vivid colors, offered a solution to the dilemma between the rigor of Academic drawing and the expressiveness of Chinese ink. A line of variable thickness outlining the volumes of the body became Sanyu’s way of reconciling Chinese painting and Western Modernism. His contemporaries Lin Fengmian and Pan Yuliang (one of the most famous women artists of that period) similarly embraced a form of pictorial syncretism, inspired by the artistic movements flourishing back then in Paris. Sanyu and Pan both spent the rest of their lives in Paris, suffering financial struggles. Today, Sanyu is the most highly valued Modern Asian artist: His work Five Nudes, painted in the 1950s, reached the record price of 38.8 million USD at Christie’s Hong Kong in 2019.

Other Chinese artists who studied in Paris during the interwar period, such as Xu Beihong and Chang Shuhong, chose instead a style faithful to the language of academic realism and became advocates for a more descriptive form of painting, favoring historic subjects and formal portraiture. After 1949, French-originated academic realism was integrated into the People’s Republic system of art education and merged with Soviet-style Socialist Realism as the official visual language imposed by the Chinese Communist Party on all artistic production.

Another group of art students, who had been educated in China during the 1930s by the generation of artists who had spent time in Paris, arrived in the French capital after World War II. While New York was slowly taking over as the art capital, Paris remained a sought-after destination for international artists, attracted by its historical avant-garde tradition, and the nonconformist character of its art scene.

One of them was Zao Wou-ki, arguably one of the best-known Chinese painters in the West today. Zao arrived in Paris in 1948 after studying at Hangzhou Art Academy, which was founded by Lin Fengmian. Another internationally established artist, Walasse Ting, arrived in Paris in 1952. By then, the atmosphere in the French capital’s art scene had changed substantially: many artists had rejected figurative art, as abstraction offered a way to free oneself from the rhetoric of previous artistic expressions, and the troubled period with which they were associated.

Asian calligraphy and painting offered a source of inspiration to European artists stimulated by the gestural style of American Abstract Expressionism. Asian artists, who in the 1920s and 1930s had been virtually ignored by the French artistic community, suddenly became sparring partners, bolstering painting practices that focused on the physical energy of the brush. This interest validated the efforts of Chinese artists to reclaim their own tradition while contributing to contemporary art trends. Ting, a close friend of Sam Francis and Joan Mitchell, mingled with a heterogeneous group of international abstract painters, including Pierre Alechinsky, whom he introduced to Asian calligraphy. Alechinsky was enthusiastic about it, and would later integrate written words and scribbles in his composition. In turn, he introduced Ting to the international CoBrA Group, which was founded in Paris in 1948, and considered the European response to Abstract Expressionism.

Zao Wou-ki’s works of this period display a gradual rejection of figuration, focusing instead on the graphic quality of dry ink drawings that dissolve in areas of bright colors. Figurative details are scattered in minimalistic compositions, disregarding accurate spatial arrangements. In these works, Zao’s references illustrate his interest in both Chinese and Western iconographies: One could tie them both to Paul Klee and 14th-century Yuan dynasty landscapes.

The radicalization of the political climate in the People’s Republic of China and the international isolation that occurred after the launch of the Cultural Revolution in 1966 brought the flow of artists from China to Europe to a halt until the end of the 1980s. With the end of the Maoist period and the reforms initiated by Deng Xiaoping, artists from China were able to travel to Paris again, sometimes with the sponsorship of French cultural institutions. An important occasion came with ´Les Magiciens de la Terre’ in 1989 at the Centre Pompidou –the first contemporary art exhibition in France to highlight artists from the Global South. Huang Yong Ping and Yang Jiechang, both by now established artists, were included in the seminal show. They traveled to Paris for the occasion, and decided to remain in France, concerned as they were, by the events that had unfolded in Tiananmen Square the same year.

The period saw a new community of Chinese artists arise in the French capital, centered around the figure of critic and curator Hou Hanru, who also arrived in 1989. The group included Chen Zhen, Yan Pei-Ming, Shen Yuan, and Wang Du; it gradually emerged as a familiar presence on the Paris art scene. At a time of increasing artistic globalization, the intercultural themes these artists addressed seemed to appeal to local audiences.

The history of this contemporary community of Chinese-born Parisian artists has recently been the subject of an exhibition at the Musee de l’histoire de l’immigration in Paris, curated by Hou Hanru and Evelyne Jouanno, titled ‘J’ai une famille’. It refers to the close ties created among the members of the group, many of whom are now globally recognized. As Hou states in a text introducing the show, they ‘shaped themselves across China and the West.’ From Sanyu’s limpid 1920s nudes to Huang Yong Ping’s gigantic snake skeleton meandering through the Grand Palais in 2016, Hou’s words ring true for them all.

Dr. Francesca Dal Lago is an art historian specialized in Chinese Modern and Contemporary art. Based in Paris, she lived in China during the 1980s and early 1990s, a time of major cultural and artistic changes. Her research and writing focus on global artistic circulations of people and objects in France from the late 19th century to the present.

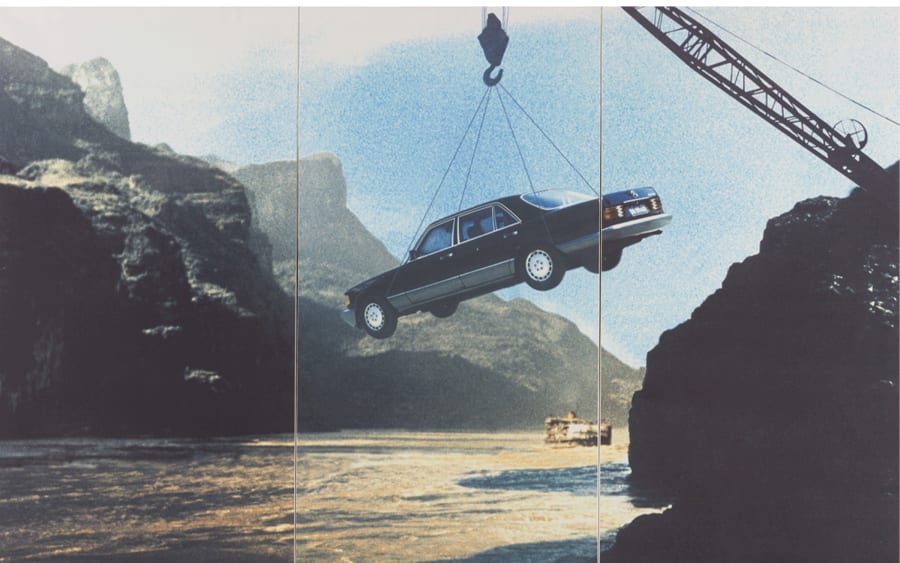

Caption for top image: Detailed view of a work by Walasse Ting, presented at Alisan Fine Arts' booth, Galleries sector, at Art Basel Hong Kong 2022.